THE FATE OF A GENERATION IN THE SYMPHONIES OF MIKHAIL NOSYREV

by Natella Kazaryan

From an office memo of the First secretary of the Russian Composers’ Union Dmitri Shostakovich to the Secretariat of the Russian Composers’ Union:

“I have heard the following works by Mikhail Nosyrev:

- Symphony.

- Ballad about a dead warrior.

- ‘This should never be forgotten.’

I have also read the conclusions of the Organizing and creative commission of the Composers’ Union of the RSFSR which has refused to admit comrade Nosyrev into the ranks of members of the Soviet Composers’ Union. I do not agree with the conclusions of the Organizing and creative commission. M.I.Nosyrev is, undoubtedly, a talented composer with sufficient professional training: therefore I plead with the secretaries of the CU of the RSFSR to hear the works of M.I.Nosyrev.

As for me, I consider that M.I.Nosyrev should be granted admittance to the USC (Union of the Soviet Composers).

D. Shostakovich. 1967”

An open recognition of talent of one composer coming from another one is always a solemn and responsible act. But the recognition of a genius, Dmitri Shostakovich, has a particular significance. This is both a high-quality mark and an enormous credit for future creative deeds.

For Mikhail Nosyrev, the Russian composer of a post-Shostakovich era, the recommendations of the author of “A Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk” were a hundred times more significant than for any other musician. The same is true of his admittance to the Composers’ Union of the USSR in 1967.

Most modern people of the present-day Russia, as well as of the developed countries of the world, would not understand to the full the degree of joy and pride that the 43-year old composer, the conductor of the opera theatre, and a rather well-known Voronezh composer felt about his admittance to the professional creative union. But it is only now that Russian musicians, men of letters, artists and journalists have every right to live independently from the state and to rely solely on their powers, talent and luck. In the USSR in the 60's the membership of a creative union was equal in significance to the membership of the central bodies of the Communist Party, and without the membership the public life of an artist, no matter how talented he/she was, was absolutely impossible. Publications of the works, concert or theatre performances, tours, recognition of artistic gifts, and commissioning of works were out of the question.

For a professional musician the membership of the Composers’ Union was vitally necessary. For Mikhail Nosyrev this was an almost-unattainable, frail dream, since Mikhail Nosyrev in his country was a “non-person”. Actually, the state has already driven him into a remote corner and would have deprived him of everything but for the laziness of its employees.

At the same time, fate had drawn a great future for Mikhail Nosyrev. He was marked out by the very fact of his birth in the most beautiful city of Leningrad (now Saint-Petersburg) in the years when many people were under the impression that the dawn of a new, happy life was breaking over the earth that had recently recovered from the World War.

As a small boy, he had all the reasons to dream about the outstanding achievements, for he was endowed with a rare combination of equally rare human traits. Mikhail possessed a marvelous ear for music, an in-born sense of rhythm, plasticity, and artistry and in addition a kind and sensitive soul and a keen intellect.

He had almost no need to study in the usual meaning of this word: to continuously and minutely develop artistic skills. He played violin and piano freely and improvised music pieces. He learnt from the great masters their great and significant deeds. This might actually have been the case; Dmitri Shostakovich lived and worked in Petersburg at the end of the 30's and the beginning of the 40's of the twentieth century, and Yu. I. Eidlin taught violin.

However, Nosyrev had no opportunity to learn from these coryphaei, although his graduation with distinction from a 10-year secondary school in 1941 was at the same time admittance to the Leningrad conservatory. Of course, it is regrettable that Beethoven did not take lessons from Wolfgang Mozart: nevertheless, he became BEETHOVEN – the way of a genius hardly depends on favourable or unfavourable external conditions.

Something similar can be discerned in the fate of Mikhail Nosyrev. Fate assigned him different universities, austere and highly dangerous. That is why, perhaps, he perceived his only meeting with Dmitri Shostakovich in 1967 as a great and inexplicable miracle. The meeting truly lent wings to Mikhail Nosyrev, blessing his outstanding creative work in the coming fourteen years.

Unfortunately, in the history of the Soviet Union the humiliation of great artists, men of letters, composers and actors was rather a norm than an exception. The lack of freedom rigidly limited the flight of imagination of all artists. Some of them were to learn the lack of freedom physically. Gumilev, Mandelstam and Meyerhold gave their lives for dissent. Many, Alexander Solzhenitsyn among them, served sentences in Slatin’s gulag.

The adult life of Mikhail Nosyrev began with arrest and a death sentence, which was then commuted to 10-year imprisonment in a concentration camp. Such a severe penalty was administered by the state to a 19-year old only because he, having been born with a pure soul, wrote down his thoughts frankly in his diary. At that time he was thinking in terms of the ideas that at present are being taught in all Russian schools and institutions of higher learning

He deeply felt that the art in the country, completely isolated from the world, intimidated and run down by a rude political ideology, was sinking into a barbaric state, having at the same time unparalleled human and artistic resources as its assets. And he, like the small child from the fairy tale, exclaimed: “But the emperor has nothing on at all!” And for this he was sentenced to death.

Now this story seems improbable in its unparalleled cruelty, but at that time, in 1943, the incident was seen as a “just punishment” of the state machine with respect to its enemies.

When serving the sentence in the far-away town of Vorkuta at minus 40°C in wintertime, Mikhail Nosyrev must have endured double sufferings: he suffered both from a deep sense of guilt for his right thoughts and from the offended feelings of a strong man betrayed by his motherland.

Vorkuta, nevertheless, was also associated with joyous emotions. First and foremost, he was alive. Second, he was admitted as a violinist and composer to the Vorkuta theatre that put on musical performances: operas, operettas and numerous concerts. The opportunity to live a life connected with music – to play violin in the orchestra, compose incidental music, carry out his creative plans – was for Nosyrev a complete happiness. He was ready to work 24 hours, “forgetting sleep and food”.

Since the First Symphony written in 1965 was preceded by 20 years of self-denying creative work, it is not surprising that in it Mikhail Nosyrev appears a mature master and an outstanding musical dramatist. The composer went through an austere experience on his way to a great art.

At the time of the crucial meeting of Nosyrev and Shostakovich the latter was 60 years old. He had just completed the Thirteenth Symphony that included the then popular expression in the male-voice settings “Fears are dying out in Russia”. A 42-year old Mikhail Nosyrev could have seemed to him a late beginner. But every artist goes his own way and plays his own role in art. Nosyrev was to reflect in his music the experience that the great Shostakovich was luckily spared – the psychology of a condemned person, the psychology of a prisoner and the psychology of an “outsider” in his own country.

Mikhail Nosyrev did not live to see the public premiere of his First Symphony. It was first performed in 1999. No one knew anything about the composer’s years of atrocity. This topic was never discussed, and Nosyrev confided in no one. In 1965, we knew him as a cheerful, bright man, a man of the world. Could we understand the artistic idea of this work?

This is an almost classical cycle consisting of an effectual sonata allegro, a philosophically-elevated adagio, an enchanting scherzo and a vivacious finale. The forms of movement are also easily recognizable: sonata, a complex ternary form, and rondo-sonata. Nevertheless, even the supremely talented Miaskovsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich would have never created such a conception. It is the parameters of the fate of Mikhail Nosyrev that determine the innovative nature of this composition.

THE FIRST SYMPHONY

Mikhail Nosyrev’s First Symphony opens a Pleiad of large and significant works of the composer. By that time the life of a talented musician settled into its more stable and straight routine. As a conductor of the Voronezh Opera and Ballet Theatre, he was constantly studying the scores of the outstanding masters and writing his own music. Tchaikovsky’s “The Nutcracker” was his favorite production, which he loved not only for the excellent music but also for a surprising closeness to this fairy-tale character of Hoffman.

In 1964 the composer was 40 years old but because of the 10 gulag years he was just beginning a normal human life. After a huge break in studies he had to master the basics of musical skills on his own. But already in his First Symphony Mikhail Nosyrev is a mature master of symphonic style, possessing a wonderful sense of musical form, a complex symphonic dramaturgy, a sense of an orchestral colouring and a sufficiently original language.

This was the time when symphonic music in this country has reached its peak. In many regional centers like Voronezh, Nizhny Novgorod and Novosibirsk, full symphonic orchestras became truly professional. Posters bore the names not only of the most popular world masters, but also such names as Debussy, Stravinsky, Honegger and Bartok. The creative work of Shostakovich was at its height, having received at last a complete “official” recognition. Prokofiev, Miaskovsky, Khachaturian and Sviridov were very popular, as well as young Shchedrin, Kara-Karaev, Eshpai, Boris Tchaikovsky, Slonimsky, Tishchenko and Gavrilin. The works of Schnittke, Denisov and Gubaidulina were actively forming the Russian “underground” musical style.

Recall that one of the scandalous first performances of Alfred Schnittke’s music was connected with Voronezh, where in 1968 the conductor Yuri Nikolaevsky and the violinist Mark Lubotsky made an attempt to perform a new Violin concerto written by this young composer. But the first performance did not take place, although the Voronezh philharmonic orchestra was experienced enough in playing the sophisticated music by Britten, Pyart and even Webern. However, Schnittke’s original musical language was understood neither by the orchestra musicians, nor by the local cultural “leaders” – the concert was simply cancelled in spite of the author’s arrival.

Mikhail Nosyrev’s First Symphony was being created in such an atmosphere. Understandably, the philharmonic orchestra would not dare to perform the composition of a practically unknown author, watched over by the KGB. Therefore Mikhail Nosyrev talked the musicians of his opera theatre orchestra into studying the symphony and conducted the amateur recording, which was presented to Dmitri Shostakovich, who was able to discern in it a true talent and originality.

Hearing this symphony now, almost 40 years later, one cannot help wondering how much and how deeply the composer could tell in it about his time and his fate. There is no doubt about the autobiographical character of the narrative. True, at that time neither the listeners, nor the critics could detect the autobiographical basis of the music. In everyday life, in communication with friends, colleagues and acquaintances Mikhail Nosyrev was always open, friendly and warm-hearted, always smiling and gently joking about himself and the topic of conversation. Therefore it was impossible to draw from him the secret conceptions of his musical epic works; at least in his description they had no such powerful philosophical and ethical meanings. The deeply-rooted content of the symphony became truly evident only in the light of the whole creative life of Mikhail Nosyrev and under the conditions when it became possible to talk about and reflect upon the reverses of his fortune. It is only now that we see that the meanings of the symphony reflect the tragic picture of life of whole generations of the Soviet people who painfully and acutely felt the impossibility of an adequate realization of their spiritual powers, a constant threat to the personality’s existence and an all-penetrating shadow of the “zone”.

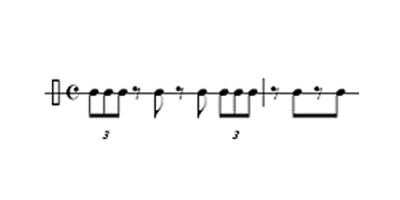

The main dramaturgical conflict of the symphony is expressed extremely visibly and symbolically, since two main images penetrate its traditional four-movement cycle: a bright expressive theme of the principal part of the first movement personifying the artist’s personality and a stark deathly rhythm of timpani, characterizing the soulless machine of the totalitarian suppression. We can realistically give such semantic interpretation to the timpani’s rhythm by the analogy with Mikhail Nosyrev’s Fourth Symphony (1980), in which a very similar rhythmic formula simply copies the international signal SOS transmitted into the air by Morse code:

Symphony No.1:

Symphony No.4:

The difference lies in the fact that in the Fourth Symphony the rhythmic formula is a materialized signal of a deathly threat, whereas in the First symphony this is rather a musical projection of an imminent and unavoidable danger.

The First Symphony appears to be quite traditional, as was already mentioned. The first symphonies of the greatest masters (for example, Prokofiev and Shostakovich) have the same classical form. However, a deep analysis exposes a rather non-standard hidden program directly denouncing the time and totalitarian regime, under the conditions of which this outstanding and talented artist was doomed to live.

In the first movement the sonata form of the traditional Beethoven type with all parts, development and dynamic reprise is realized. The movement has a small introduction, whose intonations and rhythmical figures are then developed in some fragments of all other movements. Against a future tough and austere theme of the principal part the impressionist colouring of the introduction appears as a sharp emphasizing contrast.

The principal part is presented in the form of a widely developed fugato, which is rather unusual in its way. A tonal plan of the parts’ entrances is also unexpected: after the theme is introduced by first violins, second violins respond in the main A minor tonality (imitation at the prime) and only the third development by violas is given in the subdominant D minor. The fourth development by cellos and contrabasses brings back the initial A minor. Thus, three of the four theme realizations consistently expose the main tonality, which indicates some inner constraint inherent, obviously, in this, prima facie, rather active and tough melody:

Even more unusual is the fact that having reached the climax, fugato unexpectedly is cut short, leaving place for a cold and ominous rhythmic formula of the timpani. It is as if this intrusiontells us that self-development of a personality is impossible. A blind external power follows every individual and is always ready to curb the activity of a too-enthusiastic artist. The composer, by an almost complete coincidence of the rhythmic formula with the SOS signal from the Fourth Symphony, as it were constructed an arch of his not-so-long creative road, providentially laying a bridge to his life’s finale.

The intonations of the principal part continue to sound after the intrusion of the rhythmic formula (in the connecting part), but they somehow immediately fade, grow weaker, go from the zone of full fortissimo to piano, losing any features of tonality – the action of a brutal force reaches its aim. The reaction to it is the transition to the sphere of lyricism, reveries, and fragile night dreams in the subsequent secondary part. Only the man who himself learnt the destructive power of a totalitarian state machine could construct such an exposition of a sonata form.

At first the theme of a secondary part sounds in a solo flute as regular crotchets, it is as if wound for the infinite sequence of the intonation moves repeating themselves and demonstrating that even the repose is painful, almost somnambulistic or even depressive. Further on the sounding of the secondary part becomes stronger and reaches a great force. The development breaks into the flow of the secondary part as unexpectedly, as the rhythmic formula into the principal part. The deformed intonations of the principal and secondary themes are joined in contrapuntal juxtapositions.

However, it is interesting that it is in the development with its dramatic tension and explosiveness that the composer introduces the brightest and most sonorous fragments, picturing the state of happiness and the elevated self-assertion (figures 15, 17 and 21). But their flow is penetrated by a deathly rhythmic pulsation of the formula, which prevails in the end and is announced in the general culmination by full orchestra (figure 23).

After that comes a sudden change in the imaginative development of all the parts: the principal one loses its imperative nature – it sounds in the solo clarinet against very soft muted violins and a harp, like a phantom from another world. After the next rhythmic formula the intonations of the principal part disappear altogether, replaced by a new thematic development – a chromatic chorale of the strings. This sharp fortissimo chorale is a symbol of a protest against the pressure of the evil force. However, nothing can change the situation: neither the reminiscence of the introduction’s intonations, nor the fleeting tune of the secondary part in the main A minor key – the rhythmic formula rules completely in this icy and cheerless world.

The second movement – Andante – opens with an artless diatonic melody played by a solo oboe in a folk Russian style. But very soon this idyll starts to dissipate, giving room to a harsh chromatic material and cutting grotesqueries of a bass clarinet and low strings. Only the chorus of French horns manages to bring back the diatonic harmony of the main tune. The recaptured bright space is filled by naive reminiscences of en plein air music in the style of the early Tchaikovsky. Nevertheless, the icy rhythmic formula ingratiatingly intrudes into the ending of this part with its farewell intonations dying out in the part of a solo violin. Immediately the evil images come to life in the sharp turns of a low and menacing bass clarinet. Even the restored initial theme starts to get deformed and break into separate disconnected tunes.

Now at the end of the movement across the rhythmic and timbre pattern from the trio (allusion to Tchaikovsky’s theme) the reminiscences from the Russian accordion folk-tunes are sounding; in their turn they are juxtaposed by the initial intonation from the principal part of the first movement. The fact that its tiny fragment sounds in solo oboe, opening this movement, attributes to the last bars a symbolic and deeply personal meaning – the protagonist can watch the distant nostalgic pictures only from far away and through a narrow space of one(!) bar.

The third movement – scherzo – is filled with phantasmagoric visions, changing each other kaleidoscopically. But through the crowd of these either demonic or caricature-grotesque masks, first timidly, and then braver and braver a melodic element from another world is pushing through. It is simple, naive, but enchanting due to its freshness and hope. The motifs of the first movement break through the general stifling flow, but they are as if washed away by the wave of sharp, dissonant layers.

At the same time the triplet carcass of the rhythmic formula gains force and again is scanned to forte by full orchestra. This powerful imperative rhythm stops the course of the scherzo. The sonority sharply subsides. In the state of prostration, as if from the depth of the subconscious, arises one of the intonations of the introduction’s theme. Heavy phrases of bass clarinet in low register are again reminiscent of evil images of the second movement. And suddenly, as if from non-existence, there appears in the clarinet’s timbre a touching waltz melody, which tried to break through the phantasmagoric visions. These are bright recollections of a youth about the pre-war years, when music was playing in the parks and the whole world was seen in rosy and azure hues.

The composer finds a new and bold technique for the scherzo form. Usually after the trio there followed the reprise da capo, or at least a full-scale dynamic reprise, but Mikhail Nosyrev gives only three ominously sounding bars. Triplet figures of the fortissimo timpani again bring back the rhythmic formula, crossing out all bright reminiscences.

The symphony’s finale opens with bravura fanfares of the trumpets, after which immediately comes the principal theme of the movement – the galloping circus melody with a somewhat grotesque emphasis on the tritone A- D-sharp. The second theme – the secondary part – is one more allusion to a popular music, slightly reminiscent of the well-known musical-eccentric cadences by Nino Rotta in Fellini’s films “Le Notte di Cabiria” and “Otto e Mezzo”.

It seems that the composition the takes the course of the so-called “optimistic finale” with its jocular sparkling passages. Its steady course continues until the reprise of the secondary part. However, suddenly a deathly scanning of the rhythmic formula thickly envelops artless phrases of this theme. It seems to draw one into a funnel and strangle in a sticky embrace. The chorale of trumpets and trombones cuts off the hitherto non-stop flow. The rest of the instruments try to restore the principal theme of the finale, but the trumpets’ fanfares sharply transfer the rhythm of the principal tune into the triplets of the rhythmic formula. A harsh unison of three fortes scans now the principal part theme of the first movement, reminding us of the symphony’s protagonist and his unsolved life problems. Unfinished, the leitmotif is cut short by a tutti announcement by full orchestra of loud strikes of the omnivorous rhythmic formula.

The end… The dreams, impulses, reminiscences, sufferings of the soul – everything is stopped dead and swept away by the monstrous suppression machine. Ahead is only emptiness, expressed by a stark roar of the timpani and a short unison “A”.

Such a sudden turn of events practically at the end of the composition is a bold innovative technique of the musical dramaturgy. But the composer has already preset the logic for this technique: in the preceding scherzo the elegiac waltz trio is obliterated by a three-bar phantasmagoric cadence even more impetuously. The same is true about sharp turns of imagery at the dividing line between the main and connecting parts, exposition and development of the first movement, in episodes of Andante.

Such a system of emotional catastrophes reveals most accurately the disposition of the artist who had gone through the hell of the gulag and who lives constantly on the threshold of the omnipresent trouble.

The evidence of the time, given in the First Symphony by Mikhail Nosyrev can be compared in force and significance to the well-known literary memorials by V. Shalamov, V. Grossman and A. Solzhenitsyn. This score is not only an outstanding artistic achievement, but also a vivid historical document of the epoch.

THE SECOND SYMPHONY

The second symphony was written 12 years later. During those years the composer was preoccupied with incidental and instrumental music. At that time it seemed that Mikhail Nosyrev found his calling in these more democratic genres, which suited his talent perfectly. He possessed a vividly expressed sense of rhythm, a sense of a rich orchestral colouring and he could easily entice the listeners with the course of musical events.

In the summer of 1975 the death of Dmitrii Shostakovich made a strong impression on Mikhail Nosyrev. In his subconscious he suddenly realized that he might not have time to tell the world about the most important things that nobody but himself could best express. Symphony was the only genre that could serve his purpose to express in the most concentrated form the concepts of life and philosophy.

In 1977, when the Second Symphony was written, we witnessed the birth of a truly symphonic composer. The symphonic searching preoccupied all his thoughts. New works started to appear almost every year. He met his death at the moment of the intensive preparations for the Fifth (alas, unwritten) Symphony.

By the time of the Second Symphony the musical language of Mikhail Nosyrev had greatly changed. It became more tough and graphic. He got interested in dodecaphonic and aleatory techniques of writing. The traces of this turn are already seen in the external structure of the Second Symphony: only the finale is written for full orchestra, whereas the first three movements are written for the strings, woodwinds and brass winds, respectively. This somewhat formalized idea has, apparently, a deep meaning: the world is shown as if broken into completely isolated parts, and it is the force of the composer’s willpower that unites it into one initial whole.

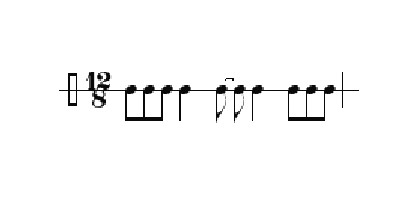

The Second Symphony is dedicated to the memory of Dmitrii Shostakovich. The dedication has its real expression in the citation of a well-known monogram D S C H. The monogram is presented at the end of the first movement and at the end of the finale, but it is gradually prepared by the themes of all movements. This is already felt in the leitmotif of the first movement, which has a tough dodecaphonic nucleus. Here other notes and sharper intonations are used (including the shorter octave), but the direction of the melodic line is the same as in the theme D S C H (by the way, the sounds of the timpani are a stylized reflection of one more great symbol – monogram B A C H):

The idea of the “the world’s disintegration” is also supported by the interchanging solos of first and second violins, viola, cello and contrabass, positioned at the place of the secondary part. Each instrument in a musical language tells its own version of the events, not connected with other versions.

The succeeding separate and mutually contrasting fragments Allegro gracioso, Andante, Allegro moderato, Adagio, Andante, Moderato complete the main idea of the movement. However, unexpectedly, in the last fragment for cellos and contrabasses the leitmotif is back and it results in the monogram D S C H, sounding suppressed pianissimo in solo cello and contrabass together with timpani.

Thus, the ordering of the text proceeds only by the external, volitional efforts, and the monogram becomes a natural external symbol of another life going on somewhere far away.

The second movement – Vivo – is written wholly for the woodwinds. This is a typical malicious scherzo reminiscent of the analogous sections of Chopin, Mahler and Shostakovich cycles. The trio in this movement, written in Andante tempo, is very interesting. Tough, deathly accords (including twelve-part accord complexes) alternate with a deathly tapping of keys of the wooden instruments. To some extent, this original technique reminds one of the strings bowing in “Symphonie fantastique” by Berlioz, who characterized the sounds as a rattle of skeleton’s bones. The reprise of a complicated three-movement form introduces no new ideas, fixing the sinister, infernal character of this movement.

The third movement – Andante – is written solely for brass wind instruments. The rotation of the main tune in solo trumpet resembles a slow waltz. Besides, here one more analogy with the Shostakovich style is seen – it is A minor with a whole series of low steps (II, IV, V), typical of a specific tonal system of Shostakovich. Here also Mikhail Nosyrev demonstrates a number of unusual techniques. It is a thirteen-voiced aleatory fugato (probably, in memory of a thirteen-voiced canon from the development of the first movement of the Eighth Symphony by Shostakovich). It is also an introduction into the score of the conductor’s baton tapping the desk. The latter technique reminds one of the situation, when a conductor is obliged to stop the poorly rehearsing orchestra – he always taps a baton out of the orchestra’s rhythm, otherwise, no one will hear his tapping. On the other hand, this non-coordinating tapping calls up the deathly rattle of the keys from the preceding movement.

On the whole this movement is a genre episode, depicting a discordant rehearsal of the brass band before a performance. However, at the end of the movement the musicians try to summarize their rehearsal and they play the principal theme as discordantly, as at the beginning, but very confidently and solemnly, which produces a comic effect.

The final Allegro opens with a gigantic 24-voiced fugato with the intruding instruments of the string and woodwinds groups. When all parts of the fugato come into one focus, all brass instruments play fortissimo, announcing the symphony’s leitmotif. The essence of the subsequent Presto lies in the alternation of sharp spasmodic sound elements and the prolonged and painful pauses in full orchestra. At some moment these spasms are subdued, and all the sound space appears to be filled with a heterogeneous chaotic sound stream. But the swirling of the uncontrolled emotions leads once again to deep painful pauses putting an insurmountable obstacle before the protagonist. By the end, like far-away, faded reminiscences, appear the themes of all movements, and the waltz theme and the leitmotif are developed in bass clarinet pp and ppp in its lowest register, symbolizing the fading and the irreversible transformation of the images.

The closing monogram D S C H is given in low cellos, contrabasses and timpani against the 12-tone cluster of the remaining strings.

The detached, indifferent sounds of the monogram call to mind once again the eternal motion of the Cosmos, in which the human passions and tragedies appear as transient and vain.

THE THIRD SYMPHONY

The conception of the three-movement Third Symphony, created just a year after the monumental Second Symphony, develops, to some extent, the ideas of the latter. Dodecaphonic themes, super polyphony, a supremely sharp harmonic language become the composer’s habitual expressive means. True, against sharply modern soundings more common, sometimes diatonic intonations and chords are used.

The first movement – Adagio – starts with the exposition of the principal theme of the work, symbolizing, like in other works, the inner world of a protagonist. A typical fifth E – H of the bassoon and contrabassoon in the extremely low register is reminiscent of the somber introduction to the first movement of the Sixth Symphony by Tchaikovsky. Against this somber background the bass clarinet leads the symphony’s leitmotif. Its three contrast elements show the tense battle of emotions: first, an indecisive swaying near the sound G, then a sharp ascent F-B-a and also a sharp fall to the lowest sounds Cis, E:

Gradually this theme is being deformed. From its tense development appears, like the sun glint from behind the storm clouds, a lyrical theme of the principal part. A solo flute plays the theme in complete silence. Diatonicism and simple song intonations contrast with the initial leitmotif. However, its slow movement is unexpectedly interrupted by a specific ominous rhythmic figuration containing a rapid unwinding, like a deformed spiral. This image, which will further appear several times, calls to mind, by its manifestation and dramatic role, the First Symphony’s soulless, mechanistic rhythms, destroying every living thing.

The restored leitmotif, the rhythmic figuration and the lyrical theme of the principal part enter a sharp dispute, followed by phantasmagoric apparitions and whirlwinds in Presto tempo. This dynamic episode leads to a reprise, in which the leitmotif, the lyrical theme and the unwinding rhythmic figure are developed, as if reconciled.

The second movement – Andante – also opens with a somber sounding of the bass clarinet in an extremely low register. Here there is a lot of fantastic and enigmatic tableaux based on the unexpected changes of factures, timbres, registers and thematic elements. This kaleidoscope of images is followed by a powerful 20-voiced canon, whose parts enter by the rules of dodecaphony, juxtaposing in super multi-part harmonic combinations. The rhythmic figure of the canon’s motif is slightly reminiscent of the unwinding figure of the first movement, and the mechanized addition of more and more new instruments symbolizes the inevitability and omnipotence of the evil force.

But the menacing avalanche, crowned by the alarm bell ringing, retreats and in the formed sound vacuum there appear scrappy intonations of the lyrical theme of the first movement. Thus, the situation is created for the similar ending of both movements – a soft fading chorale of the strings. Only at the end of the second movement against the chorale the glockenspiel’s sounding is reminiscent of the canon’s motif, but it is already weakened and torn by pauses. The composer uses these dots as if to say that the evil is close by, it hides and waits for the occasion to come back.

The principal theme of the finale, announced by the clarinet, calls to mind, by its decisive character and the dodecaphonic structure, the leitmotifs of the First and Second Symphonies. The intensive development of this theme is opposed by the part based on another dodecaphonic material, imitated by the strings. The wealth of pianissimo trills and tremolos make this image enigmatic. However, at the end both the themes acquire the solemn and emotional character, which is not weakened until the end of the score. Thus, for the first time in the symphonic works of Mikhail Nosyrev an attempt is made to give an optimistic colouring to the finale. But the triumph of these positive forces is still painful and feverish, bringing neither esthetic nor dramaturgic satisfaction.

Probably, this is a “Pyrrhic victory”, when a protagonist is forced to reject his true self and accept the rules of play of the evil and treacherous world surrounding him. Anyway, the image of the lyrical theme of the first movement, that of a true light, is replaced in the “victor’s” consciousness by harshness and outer bravado.

THE FOURTH SYMPHONY

The two-movement cycle of the Fourth Symphony closes the creative activity of Mikhail Nosyrev both in terms of chronology and conceptions. The first reviewer of this work V.Devutsky defined it as “catastrophe symphony” and compared its tragic sounding with such colossi as the Sixth Symphony by Tchaikovsky and the Sixth Symphony by N.Ya.Miaskovsky.

It may seem that the two-movement structure weakens the dramatic potential of the work. But in the context of all symphonic canvases of Mikhail Nosyrev the structure of the Fourth Symphony is quite sufficient for the realization of the tragic idea.

The opening of the symphony is unusual. It is a magic painting reminiscent of a sweet dream with fantastic unearthly visions. A soft tinkling of four triangles immediately sets a fairy-tale tonality of the introduction. The glockenspiel, bells, piano in a high register, high harps, cellos and other strings, entering by turns, strengthen this colouring until a sharp fortissimo of contrabasses at the extremely low C of a contraoctave and the thunder of timpani break this vision. At the same time a solo trumpet franticly declares a dodecaphonic theme reminiscent of analogous leitmotifs of a protagonist in the preceding symphonies:

The only difference is in the fact that this melody is extremely harsh and categorical, as if cut out of stone. During the exposition of the main part it appears three times, always in the timbres of brass winds, practically never changing its original form. Parallel to this, the whole aleatory bacchanalia of grotesque and evil images, imposed one upon another, break out in the orchestra.

It is the secondary part that gives some softening of the sounding. Sequentially the French horn, trumpet and trombone at piano lead new dodecaphonic themes, in which the intonations of the principal theme are heard. At the very end of the exposition, against the chorale of low strings, the bells at pianissimo ring mysteriously both the secondary and the main melodies.

The intensive development brings the leitmotif to the timbres of woodwinds. Its separate fragments are heard in cor anglais, clarinet, and bassoon until it again passes to French horns. The chorus of all brass winds brings this melody to a climax, then it is cut short, and in the ensuing silence the softest sound of a solo violin is heard. The violin plays another dodecaphonic melody, close in spirit to the secondary part. The tutti of the strings and woodwinds tries to muffle it, but gradually the violin’s part grows stronger, and further on this theme sounds in a thick chorale of high strings.

The second wave of the development is represented by a 30-voiced canon, accumulating a great energy, followed by a reprise of a synthetic type: against the magic sounds of the introduction the trumpet and trombone lead the leitmotif in octave. In response the strings lead the secondary part, and the trumpet, French horn and trombone once again, this time at fortissimo announce the leitmotif. The solo violin puts an end to this confused struggle by once again singing its developmental lyrical melody.

This movement ends in the fading morendo of high strings, the harp and glockenspiel. Its specific peculiarity lies in the fact that the leitmotif has practically no development; it stubbornly declares its initial position, whereas all other narration layers are in a constant and versatile motion. Besides, the principal part is shown at the moment of an emotional lock.

The second movement, like the first one, starts with the cascade of percussions: this time these are tam-tams, legno, bass drum and side drum, cymbals and timpani. The harps and piano are added, tapping dense clusters in an extremely low register, then come cluster pizzicato of contrabasses. But the most important key element is sharp, single tolls of the bell at a gloomy note Cu (the Sixth – B minor – Symphony by Tchaikovsky comes to mind once again).

Against the growing rhythmic tapping of the orchestra the bell tolls 12 times (this is specially emphasized in the score), after that the orchestra falls down like avalanche, gradually fading. The bass clarinet in the extremely low register leads one more dodecaphonic theme, in which the intonations of some melodies of the first movement are joined together.

One more climactic wave leads to an unexpected complete silence. All sounds die out, and through the numbness the rhythm of the international SOS signal breaks through, hardly discernible.

Sequentially and gradually its power grows, as more and more instruments join to produce it. The 15th SOS signal is produced by full orchestra. An oppressive silence falls in response.

Against the seething chromatic splashes of woodwinds and brass winds the trumpet and the unison of the strings lead the principal theme of the first movement. Once again a phantasmagoric action unfolds leading to a still more powerful general climax, at the peak of which the signal “Save Our Souls” sounds three times with a powerful increase and is broken by a heart-rending silence. After the third SOS follows the tragic stroke of tam-tam symbolizing the end of the protagonist’s course of life. ![]()

Mikhail Nosyrev's furious music

Out of a mysterious non-existence the magic sonority of the opening of the symphony is born created by soft timbres of glockenspiel, cup bells, triangles, two harps and a piano in the highest register. This device throws an arch across the whole symphony canvas, thematically closing the narration. But the composer builds one more arch giving the almost literal repetition of the ending of the first movement, where the solo violin sings the secondary lyrical theme. Such a dual framing of the symphony serves not only the logical closing of the cycle, but also draws clear meaningful parallels: a true fullness and beauty of life come to a man only in ravishing dreams, fancies and inner visions. Real life is harsh, vulgar and unjust. Therefore for the composer and his protagonist the words of the signal “Save Our Souls” have a literal meaning – to save a soul, for our cruel world has no means to provide a dignified existence of an individual in all its fullness, or to meet his material and spiritual demands.

So, the four symphonies of Mikhail Nosyrev clearly draw the fate of their protagonist, a man of the middle of the XX century who, notwithstanding the achievements of civilization and a technical and scientific progress, feels a constant and inherent tragedy of his existence. A clever, delicate and kind person always has to wear a mask of a trustworthy average statistical philistine. He is happy only in the moments of reminiscences or illusory dreams. The surrounding world is icy and cruel to him. Hence the harshest language of the composer: dodecaphonic themes, polyphonic non-third vertical, fundamental non-coordination of contrapuntal facture lines, mechanistic ostinato and super polyphonic canons. Hence also the most important meaningful role of soulless rhythmic figures and huge emptying pauses.

Mikhail Nosyrev’s symphonies better and more fully than any historical or philosophical descriptions expressed the tragic life perception of the people in the country, which pitilessly and in a planned manner trampled down the richest human potential.

Alongside with the symphonies of Dmitri Shostakovich this is a priceless artistic document of our epoch.

Other works by Mikhail Nosyrev are not that autobiographical. His personal kindness, good nature, tenderness, lyricism and humour found their reflection in popular themes of incidental music, instrumental works and vocal pieces. In the chorale “Nocturne”, brilliantly performed at the end of the 70ies by the Chamber Choir of the Voronezh Art Academy under the direction of Oleg Shepel, the composer amply used dozens of the most bold and at that time rare devices of chorale composition: random structure, sonority, super polyphony, polychordal technique, serial technique, onomatopoeia and others.

His cello concert, which was also brilliantly performed during twenty years by the Voronezh cellist Alexander Pokrovsky, strikes one by the force and depth of open emotions, immersion into the spheres of ethical and philosophical searching and tragic life collisions. This composition is on a par with the Second cello concert by Dmitri Shostakovich in the masterly version of Mstislav Rostropovic of the 60ies.

The quartets are of real interest. The stringed instruments were especially close to the musician’s disposition. Here Nosyrev’s talent is exposed most delicately, in a many-sided manner, attracting one by lyricism and a stormy emotional flow.

Mikhail Nosyrev’s ballet “The Song of Triumphant Love” based on Ivan Turgenev’s tale of the same title was his great success. It was written specially for the Voronezh Opera Theatre and set an original theatrical record: it was running without changes for more than twenty seasons. The ballet music – beautiful, inspired, lyrical – reflected to the full a delicate plastic intuition of Mikhail Nosyrev, his talent for a musical dramaturgy and his stunning sense of orchestra.

The ballet score breathes a full-blooded orchestra life, where all timbres are used with a maximal effect and colouring.

Undoubtedly, the death of Mikhail Nosyrev was premature. The intense creative life and excessive work of an orchestra conductor undermined his health. Probably, the cruel 40ies were also to blame. However, Nosyrev can be called a happy man. In spite of everything, he survived, found himself in an artistic milieu, and realized dozens of bold creative plans, both as a composer and a conductor. He was happy in his family life. The wife, Emma Moiseevna Nosyreva, a well-known Voronezh journalist, when a young girl, performed a deed – she fearlessly married a former convict. She helped the composer to survive at all stages of his difficult life.

The life and achievements of Mikhail Nosyrev, his contribution to the music art will continue to impress the people who will come to know his music, complicated, at times, but so sincere and powerful.

MIKHAIL NOSYREV’S VIOLENT MUSIC

by Lev Kroichik

Last Friday and Saturday two symphony concerts dedicated to Mikhail Nosyrev were held and his music was performed. The concerts were closing the festival “The Panorama of the Music Written by Voronezh Composers” and the finale was truly notable.

Opening the concert, Professor Bronislav Tabachnikov pronounced Mikhail Nosyrev an outstanding composer. In my opinion, that was no exaggeration at all. I’m not a critic of music. I’m not writing about Nosyrev’s music, I’m only describing my impressions. While listening to two orchestral Concertos by Mikhail Nosyrev ( a violin concerto was performed by Vasilii Kuvakin and a piano concerto by Igor Zhukov) I was recalling an unpretentious notebook, a diary, bearing a neat handwriting of the young man who was used to do things scrupulously. It was not just an ordinary diary to keep memories. It was a confession made by a person who rapidly matured and realized that in this world the evil dominates the good.

A poet once said that we never know what echo our words will produce. Mikhail Nosyrev’s words were echoed not only by ten years of the penal servitude but by a sharp, tragic and troubled music that irritates and is far from being delightful. Nosyrev, the composer, turned out to be not just a philosopher who grasped the meaning of our distorted existence, but in his music one hears a poorly concealed fury of the man who realizes that it is next to impossible to change this ghastly false world which feigns goodness and light.

Mikhail Nosyrev’s music is full of despair and sorrow.

The professionals might not agree with me and they might say: “Your interpretation of Nosyrev’s music is all wrong. Listen carefully: Nosyrev is cunning and lyrical, mocking and optimistic. This Nosyrev, he can be very different”.

This may be true. I won’t contradict the professionals, but Nosyrev’s irony is almost sarcastic and full of disbelief in that which is going on. The young man who survived the blockade of Leningrad could not (and would not) be reconciled to the fanaticism of the zealots who condemned many hundred thousand people to death. No, I did not hear the reconciliatory motifs in Mikhail Nosyrev’s music – the composer is storming within even years after the events he lived through.

The chronology of his work can prove it. The First Symphony was written in 1965. Its lyrical and epic intonations seem to suggest some reconciliation with the world – the war ended twenty years ago and its dramatic collisions remained in the past. But then follow the violin concerto (1971) and the piano concerto (1975) and one realizes that Mikhail Nosyrev had forgotten nothing and had forgiven nobody.

Probably the technological construction of the symphony concert made special demands on its programme (the symphony was closing the concert) but the logic of the composer’s biography resisted this construction.

And in the end it prevailed.

A powerful music composed by Mikhail Nosyrev was rolling through a small symphony hall obedient to a firm hand of Vladimir Verbitskii, the conductor, who is capable of controlling the elements. The music also seemed to convey one more motif, that of a warning.

The trumpets sounded a note of alarm. The percussions joined loudly.

There was no peace.

Outwardly Mikhail Nosyrev was a cheerful and companionable person. But, good God, what was going on deep in his heart!

The Touchstone

(Newspaper “Voronezhskii Kur’er” (“Voronezh Courier”), June 9, 2000)

By Vladimir Belyaev

At the beginning of the 70ies, on coming down from Moscow Conservatory, I found myself in Voronezh, in one of the prestigious Russian composers’ organizations. Its founding father and the constant chairman K.I.Massalitinov gave me a hearty welcome, and I tried to find my place in a mixed collective of creative people, in which the genial B.Vyrostkov and the outspoken M.Zaichikov, the always-in-a-hurry intellectual V.Gurkov and the unpredictably aggressive G.Stavonin co-existed somehow; and somewhere in between the inconspicuous and warm-hearted Mikhail Nosyrev occupied his own place. And very soon, notwithstanding the age difference, we were on friendly terms.

Our drawing together might have been the result of his interest in the work of his young colleague, but most probably of Nosyrev’s isolation. I had no idea at the time that Nosyrev was not a member of the Composers’ Union (I myself easily obtained the membership after a year or two of my work in Voronezh).

By that time Nosyrev was already a mature musician with a strong individuality, but he was looked down on as on the “ugly duckling” in the famous Andersen’s fairy tale. He became a member of the Composers’ Union much later at the insistent request of Dmitri Shostakovich. However, during 15 years of our relationship Nosyrev never spoke about his problems, never complained about his fate or injustice.

That was the epoch later called the flourishing stagnation, when the state was taming the culture workers by means of privileges and social benefits. One of the main functions of the creative unions was the share-out of the “financial pie” – the money allocated for the acquisition of the works of art and music. The practice was a destructive one, since the cost of the works was determined not by the aesthetic qualities but by the ideological standards.

Sometimes a sheer volume of a work mattered. For instance, it was possible to write a song for the party congress, to call it a cantata and to receive a royalty as for the symphony.

Mikhail Nosyrev never lost a professional dignity, he did not take “the state’s bait” and preferred earning his bread by a backbreaking conductor’s temp work – he never refused to do the hardest, the most ungrateful and sometimes utterly senseless work. Nosyrev never made comments about the ideological music written by his colleagues, admitting that everyone had his own idea of conscience.

I must confess I have no information as to whether his works had ever been recommended for the presentations at plenums or congresses of the Composers’ Union but I know for sure that he was never nominated a delegate or guest to any of them.

Meanwhile for the Russian composers the 60ies and 70ies became the time of the search for the avant-garde expressive means which in Europe were no longer avant-garde. In the USSR those techniques got the name of “formalistic” and hostile to the home culture. Today it is difficult to understand how in 1976 it was possible, at the initiative of one of the respectable masters of the Soviet music, to withdraw from circulation the book by “The Techniques of Composition in the XX century”.

The creative work of Mikhail Nosyrev was a notable artistic deed – the composer developed the ideas of the Western avant-garde, taking into account the home traditions. In the Soviet music that was the road taken by such composers as A.Schnittke, E.Denisov, I.Karetnikov, S.Gubaidulina and some others. If Mikhail Nosyrev lived in Moscow or Leningrad, he could have had a chance to become a musical leader both at home and abroad.

I remember one of Nosyrev’s stories about how he cheated the heads of the city and the audience when in his new piece he introduced the dodecaphonic motif and no-one noticed. In this way the composer proved that all the expressive means were good, the main thing was to use them skillfully. I must admit that at the time I thought his behavior boyish, since he was in danger of being found out by some musicians eager to detect those ideologically dangerous experiments.

The Voronezh music lovers still remember the events of the recent past, when directly from the rehearsal a group of orchestra musicians went to the regional committee of the Communist Party to report that they were made to rehearse the music by Alfred Schnittke. There followed a quick reaction, and the premiere was cancelled with a scandal. Alfred Schnittke was free enough to write his music openly, whereas for Nosyrev any scandal might have had terrible consequences.

In the 70ies Mikhail Nosyrev was one of the leading Russian symphonists. He used to compose music in summertime, on holiday from work, at his summer house where there was no piano. He at once wrote clean copies of his symphonies’ scores. Only a professional knows how difficult this work is and what an extraordinary skill is required for it. When Mikhail Nosyrev died leaving four symphonies behind, I was struck by the thought: what unrealized creative potential he took with him! In fact Nosyrev was the follower of Shostakovich’s traditions and he could have written lots of new music!

Two leitmotifs marked Nosyrev’s creative work – the motif of the all-conquering love and the belief in happiness, on the one hand, and the motif of life and death, on the other. The second theme was characteristic of Dmitri Shostakovich’s work. However, for Shostakovich death was a philosophical category. At one of the rehearsals he said: “I wanted to show how awful death is in all its manifestations, so that people could value and love life more”. For Nosyrev death was a reality which he faced in the condemned cell. The orchestral works of the composer convey the sensations of a man who found himself at the fatal line separating life and death. The almost physiological impact of this music is comparable with that of some F.Dostoyevsky’s works…

The atmosphere of the Composers’ Union was really inspiring. New works were given full attention, useful remarks were pronounced and the criticisms voiced. But it was Mikhail Nosyrev to whom I turned for advice.

I considered myself to be a good orchestrator after having taken the lessons from such outstanding teachers as N. Rakov, Yu.Fortunatov and M.Chulaki. But one day Mikhail Nosyrev gave me an unforgettable lesson worthy of the full conservatory course. At the time I was orchestrating my vocal cycle “The Girl’s Torments”:

I was walking through the garden,

A bird sat on my breast.

The bird sat and said:

“Forget about your sweetheart”

(Word-for-word translation)

In folk “torments” it is a laugh through tears. I wanted to create a delicate psychological picture: a dramatic realization of the sweetheart’s betrayal. The heroine of the cycle hears these terrible words as if in a dream, in a fairy garden, from a summer-bird.

Any schoolchild knows how to demonstrate a bird by means of an orchestra: it might be a flute, clarinet, oboe or reed pipe. But in this case a bird would seem real and the desirable state of irreality would disappear. Having tried hard to solve this unsolvable problem, I came to Mikhail Nosyrev for advice. His eyes lighted up, he thought for a moment and gave me the very variant I was looking for – the bird’s role should have been played by a solo cello.

Usually the cello’s sound is associated with a mild, velvety baritone human voice, and here’s a bird! But the secret lay in the technique of playing – flageolet glissando. This rare performing technique can be found in the literature for solo cello and, as far as I know, never in the orchestral works. I appreciated the paradoxical beauty of this solution only during the rehearsals – the “bird” was just perfect.

At the premiere sang the soloist of the Bolshoi Theatre Nina Glazyrina, the young Vladimir Verbitsky conducted the orchestra, and the “bird” fragment made a strong impression on the audience…

Mikhail Nosyrev left this world at the height of his creativity, as if at the most intriguing point of a phenomenal game of chess (he was a strong chess player, by the way) which no one can finish now.

In many cases children follow in their parents’ footsteps. Mikhail Nosyrev’s son is not a musician, but he can be called his father’ follower because of the colossal work he has already done in order to record and publish his father’s musical heritage. Time will be the only true touchstone of such a phenomenon in the XX-century music as “Nosyrev’s symphonism”.

Exceptional talent

(Magazine “Sovetskaja muzyka”, 1985)

G. Lapchinsky

Recently, on the stage of the Voronezh Opera and Ballet Theatre once again have come to life the characters of the ballet "The Song of Triumphant Love" written by Mikhail Nosyrev . After the performance, recalling many recitals of the symphonies, instrumental concertos, and chamber music by the prematurely deceased composer, I came to the main conclusion: his work, unfortunately, underestimated during his lifetime, nowadays continues to touch the hearts and minds of our contemporaries....

The way of the musician was not easy or cloudless; and yet, it was unquestionably a success. First, the studies at the ten-year school at the Rimsky-Korsakov Leningrad State Conservatory, then within the walls of this famous higher education institution under the supervision of such brilliant teachers, as M. Belyakov (the class of violin) and A. Gladkovsky (the class of composition). The acquired knowledge and professionalism were constantly enriched and successfully served the spiritual growth and creative self-assertion of the musician.

It would be no exaggeration to say that the musical talent of Mikhail Nosyrev got "matured" and polished on Voronezh land, in close collaboration with the staff of the Opera and Ballet Theater during more than two decades of inspirational and productive activities. The work of an opera conductor, the open-air symphonic stage performances, as well as an independent interpretation of the dozens of works of classical and modern music - all this, as often happens, steadily prepared Mikhail Nosyrev for an active music composition: time was obviously ripe for putting into practice the skills received in A. Gladkovsky's class.

By the beginning of the 60s Mikhail Nosyrev has written a number of songs, cantatas, oratorios and instrumental works. The most significant has become the ballet "The Song of Triumphant Love", which makes us dwell on it in some detail. This work (librettist and director S. Shteyn) is a choreographic version of Ivan Turgenev's famous story, which, in our opinion, had all necessary features to become the basis for a romantic ballet. For Mikhail Nosyrev it was, in fact, the first (with the exception of the written earlier one-act ballet "The Unforgettable") test of strength in a full-length genre.

If the saying is right that the fate of a composition much depends on the specific conditions under which it is created and then exists, then the ballet by Mikhail Nosyrev is a strong proof of this. "The Song of Triumphant Love" was written for the Voronezh Opera and Ballet Theatre and for many years, up to the present, has been successfully running on its stage.

Like some other compositions of the 60s, "The Song of Triumphant Love" demonstrates to a certain extent the traditional thinking of the composer (certainly influenced by the work on classical scores at the theater). This concerns primarily the dramaturgy of the ballet, which preserves the number pattern and the principle of leitmotifs that characterize the protagonists. The author's style as a whole is rather traditional, remarkable in melodies and clear, predominantly diatonic, tonal basis. Also, the music of the ballet is full of theatrical vividness and classical images; it attracts the listener by an open emotional tone and orchestral brilliance.

Besides the ballet, among the works of the 60s, another landmark in the development of Mikhail Nosyrev as a composer was the First Symphony . Being creative and self-critical, he clearly realized that in the art of the second half of this century one can hardly be successful relying only on the "stylistic zone" of the classical composers of the past, however magnificent it might be. The times compelled to actively search for a new "musical material" based on a natural mixture and finest links of the tradition with the innovations of the century in the field of melodics, harmony, polyphony, form, and orchestration. The richest experience of the Soviet masters, first and foremost of Dmitri Shostakovich became the main education for our author.

Here I would like to emphasize a few important details: first, Mikhail Nosyrev's passionate, enthusiastic and productive manner of work; spontaneity and naturalness, which characterized his search for a new stylistic way. All this showed that the composer's interest in the new sound world had long matured internally. Technically he was equipped to choose with greater freedom the means of solving a variety of artistic problems. And most importantly, the author's view of modern life became much broader and more intense. Philosophical generality and intellectual richness of his ideological and artistic intentions increased, often translating into a massive form, and the orchestral palette got significantly enriched.

One example of this is the triad of instrumental concertos for violin, cello and piano. Each is remarkable for a creative approach to three-movement series. Thus, in the Violin Concerto the two movements, Moderato sostenuto and Andante, have a lyric-meditative nature, and the finale, Presto, contributes a lush folk tint to the overall atmosphere. The Cello Concerto has different unconventional patterns too: Preludo; Moderato - theme with variations; Adagio, Lugubre, as well as the Piano Concero: Improvisata; Ritmo ostinato; Finale. Andante. But, perhaps the most artistically whole, in our opinion, is the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra. Its music captures a deeply personal note (the work is devoted to the memory of the composer's mother). The Concerto embraces the mood of the memories (the first movement), and the concentrated, sometimes excruciatingly hard thoughts embodied in the form of variations (the second movement), and an open human sorrow (the third movement). Realizing his intentions, Mikhail Nosyrev, however, did not try to fix in his music some specific details of life or any programmatic associations, including extra-musical ones; he aspired to a generalized expression of a troubled life and, therefore, to the sphere of "pure "instrumentalism. (Running a little ahead, we say that the composer remains true to this type of orchestral thinking in his subsequent works, the symphonies.)

As a result, significant changes took place in the interpretation of the themes, which becomes potentially capable of the most diverse transformations due to strengthening the role of disciplined thought. Naturally, the tonal relations are treated in a new way. However, the composer is clearly in no hurry to take his music out of the sphere of tonal attractions altogether, even when he uses very rich and dense sonorous formations.

In the structure of the Cello Concerto the third movement stands apart with its highly individual approach to a unique type of a synthesizing finale, created by the composers in the second half of this century (recall, for example, the finale of the Second Piano Concerto by Rodion Shchedrin). The meaningful summary of the work is not in a compressed retelling (with reminiscences or leitmotifs) of the thoughts from the previous movements, but in a new, sharply contrasting musical material.

The above brings us to the conclusion that Mikhail Nosyrev's creative work in the 70s not only demonstrated a close link with the best traditions of contemporary Soviet and foreign music, but also their active and successful interpretation in his own works.

Thus, already in the triad of instrumental concertos there started to emerge that individual conceptualism, which from now on will be the basis for artistic thought of the composer. Its defining elements were to be a jazzy contrast of images, psychological richness and intellectual meaningfulness, emotional explosiveness and dramatic collisions, not alien to tragedy. All this found a vivid artistic continuation in the future, in the triad of Mikhail Nosyrev's symphonies.

Creating a conceptual fabric, as is well known, is an important and crucial stage in the creative work of each composer. "Symphony is not an everyday affair, but a great gift", - said composer Anatoly Liadov. In our opinion, Mikhail Nosyrev's Second Symphony written in 1977 was his creative peak. Its music expressed sincere admiration for the creativity and personality of Dmitri Shostakovich, to whose memory the score is devoted. Needless to say, in such a dedication was, on the one hand, a highly noble idea, on the other, a great creative responsibility.

Listening to the Second Symphony, one immediately pays attention to its orchestral dramaturgy. Each of the four movements has its own unique tonal image. Thus, the first movement is in the entire charge of the string quintet with expressive solos played by the leaders of each group; the second - the woodwinds and the third - brass instruments. Only in the finale all the participants of the previous action are united in a single, powerful ensemble.

The substance of the Symphony embraces a reserved imperative (the first movement), a playful scherzo, often with a humorous tint, a genre grotesque of middle parts, and high emotional intensity with a tragic breakdown in the finale. Such a multifaceted world of images is projected through the lens of deeply personal, intimate thoughts. The Symphony coda (Lugubre) gives one a shock, causing a feeling of sorrowful irreparable loss. As in the finale of the Cello Concerto, the composer is able to sensitively highlight the eternal conflict between life and death. The musical style of the series clearly revealed the relationship with the artistic experience of the great Soviet symphonist, the creative and mature connection.

Mikhail Nosyrev's Third Symphony became the next step in establishing and securing his new stylistic principles. The basis for the first movement is a noble and poetic image of the Russian nature. Its gentle pastoral beauty is well associated with an intimate diatonic melody in the low solo flute; its sound is naturally enveloped by bassoon tints. However, in this lyrical tone-painting one hears the author's meditative intonation. The serial and aleatory sequences, twilight subtlety of twelve-step chromatic clusters serve as emotional and imaginative counterbalance. Actually, a very sharp musical dramaturgy of the series is built on the opposition of a clear song diatonicism and sonority. The second movement is a new stage of the conflict. Finale is an anticlimax in buoyant marching rhythms. The focus of the author's thoughts, it seems, does not require additional comments.

And at last the Fourth Symphony . Again, a keen interest in deep problems of human life becomes the initial impetus for the composer. And again, the desire to master a new type of dramaturgy generated by the idea of maximum compression and bold interaction between two strikingly contrasting principles: concentrated, restrained (Moderate sostenuto) and impulsive (Allegro molto). However, the slow finale of the symphony as if "matches the end and the beginning", which brings a sense of well-known symmetry into the series, a peculiarly disguised ternary form.

The Fourth Symphony is surprisingly compact, and most importantly it is one-piece, monolithic. This is due primarily to the deep and expressive themes as the basis for the intense process. Here we recall first of all an imperiously commanding motif of solo trumpet and lofty tremulous intonations in the strings divisi.

The stylistic form of the symphony is diverse. Multidimensionality of its semantic layer can, of course, cause a variety of interpretations and assessments. This is evidenced, in particular, by the responses, which the work evoked in music critics in Voronezh. However, it seems hardly justified in this case to darken too much the tragedy of the concept, as well as to over-emphasize its life-affirming pathos. The music of the Fourth Symphony, in certain proportions, synthesized both, as it was in the Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, and the Second Symphony. Perhaps, the composer, more pressingly than ever, invites the audience to feel compassion. It is important to stress that here a lively artistic intuition safely takes the author away from the danger of abstract philosophizing; his narrative about the troubled, complex emotional world is full of life and has the form of a trustworthy human confession. In my opinion, the Fourth Symphony is yet another convincing proof of the constant intense, concentrated work of the mind and soul of the composer, the evidence of his undoubted professional development.

Each completed work revealed an extraordinary creativity of the composer to a fuller extent and in a more interesting way. His perception of contemporary generously multi-sided life became sharper and deeper. The author's mind worked vigorously and rapidly. His plans for new works have matured; but, unfortunately, they were not destined to be realized. Mikhail Iosifovich Nosyrev lived spiritually intense creative life until the end. His compositions, especially those written in the 70s, struck an original note in the Soviet music.