French music magazine “Repertoire”.

Condemned to be executed in 1943 for “anti-Soviet” activities, Nosyrev served a 10 year sentence in the gulag and was only after his death exonerated and rehabilitated. On his return from the camps he became an orchestra conductor far from Moscow and a member of the Union of Soviet Composers only in 1967, thanks to the courageous and intransigent support of Dmitri Shostakovich.

Exempt from military service for poor eyesight, he took part as a violinist in the rehearsals of Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony until his iniquitous arrest in 1942. These terrible circumstances delayed his compositional career until he was 30 years old.

His 1st Symphony (of four) dating from 1965 is epic, tragic, post-romantic and it impressed Shostakovich. The 1-st movement is built on the antithesis of a brilliant and expressive theme against a stark and icy rhythm, while the second, andante, distills an underlying lyricism. The more virtuoso final allegro oscillates between the melancholy and a rhythmic liveliness.

The 2nd Symphony of 1977, stylistically more modem (using the serial technique) and in four movements, begins with an Allegro moderate resoluto – Andante – Moderate, orchestrated for strings, timpani and cymbals; its tragic atmosphere is impressive. Listening to it, one often thinks of the style of Shostakovich (to whose memorey the symphony is dedicated). The choice of grotesque passages and obstinate rhythms confirms this impression. While the “vivo” pushes the winds to their limits, a relative peace takes over in the andante for brass and percussion. The final allegro for full orchestra, whirling and virtuoso, quotes from the previous movements and ends, pianissimo, with the Shostakovich motif.

The Orchestra of St. Petersburg and the conductor, Verbitsky, free of all ideological constraints, resuscitate this painful universe, marked by anxiety, injustice, absurdity and fortunately characterised by an insatiable thirst for happiness and peace. Thanks must go to Olympia for filling an intolerable gap. The music corresponds to this sad remark: “Externally Mr Nosyrev was a happy and sociable man. But, my God, what went on in the depths of his heart!”.

Sunday Times Culture, June 20, 1999

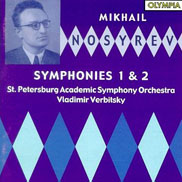

A powerful introduction to a composer unknown in this country who was a victim of state repression in his own. As a 19-year-old violinist, Nosyrev (1924–81) was abruptly sentenced to 10 years’ imprisonment and then refused admittance to the composers’ union when he came out But Shostakovich intervened and the composing career that had begun in the Gulag was able to proceed, though he remained technically a “non-person” until after his early death. He wrote three concertos’ ballets and string quartets and four symphonies. These brilliantly alive and colourful performances, recorded with remarkable depth and immediacy, show that the First (1965) and particularly the Second (1977) of the symphonies are well worth hearing. Both four-movement works of basically traditional Russian cast, they are romantic-modernist essays whose idiom veers between the full-bloodedness of Tchaikovsky and the irony and grotesquerie of Shostakovich.

Gramophone, September 1999

Last February, Mikhail Nosyrev’s First Symphony received its public premiere. Behind this simple statement lies the story of a 19-year-old composer being hauled out of a concert in 1943, sentenced to death for anti-Soviet jokes reported by his teacher – the betrayal makes one cringe – but after a period in the Gulag given rehabilitation largely thanks to Shostakovich, who in 1967 wrote an official letter speaking of him as “a talented composer with sufficient professional training”. Nosyrev died in 1981, having begun the First Symphony as long ago as 1957, never really seeing the fruits of that intervention but (as these works testify) deeply in debt to the older composer. The full tale is told in Per Skans’s thorough note to this record; and Olympia sets an example to more prestigious record companies with essays by Skans that are a contribution to the history of music in modern Russia.

Shostakovich’s voice echoes in this music. It is heard in the finale of No. 1, again in the grotesqueries of the Vivo of No. 2 (the Gogol-inspired Shostakovich of The Nose), perhaps in the ironically corny waltz in the succeeding movement, perhaps in the savage destruction of that tune in its closing bars, unmistakably in the DSCH motto theme that sounds softly here and there. There are echoes from earlier composers, too. The Orchestral reviews Andante of No. 1 is not the only music to turn affectionately in the direction of Tchaikovsky, though Nosyrev is sensitive enough to avoid pas-tiche and instead to reflect the French elegance which Tchaikovsky gratefully took as inspiration. Both works are filled with ideas, and with vividly imagined colours. No doubt recognizing his gift here, Nosyrev scores the Second Symphony as one movement for strings, one for woodwind, one for brass, and a finale for full orchestra (the percus-sion players are kept busy throughout). But I cannot avoid agreeing with DJF, reviewing the Third and Fourth Symphonies last January, that despite “vivid and memorable moments” their full potential is never realized. Nosyrev too often takes refuge in colourful splashes of invention that go nowhere, or are rather factitiously sustained for a bit in fugue. It is not difficult to shelve these reser-vations and feel sympathy for a composer who had so much invention in him, and perhaps, as Shostakovich sagely wrote, “sufficient” training, but not yet enough to make the most of his consid-erable gifts. Those who decide to give this brave and suffering composer a try will assuredly find his music of real interest.