Gramophone, September 2001

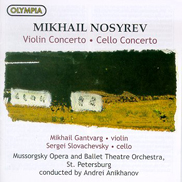

Not the least of Olympia’s services to the cause of Mikhail Nosyrev (1924–81) have been the essays by Per Skans, relating the dreadful story of his betrayal (by his teacher, of all people), arrest, imprisonment in the Gulag and eventual release. Skans has even located the actual NKVD (later KGB) document rigging the trial. He also gives very lucid and fair accounts of music we should know better. Nosyrev’s four symphonies have already been recorded; these two concertos are will worth adding to the lists.

Shostakovich is once again something of an artistic father figure, as indeed he was in person to the suffering composer. The voice of Prokofiev is also to be heard in the melodic succulence of the Violin Concerto’s Andante and more than once in a sly modulation or witty swerve on to an unexpected cadence. This, though, as with some movements in the symphonies, is a piece that packs in almost too much invention without making the most of it.

Not so the Cello Concerto, an altogether graver and sadder work despite the lively central theme and variations. On either side lie two beautifully sustained Adagios, drawing on simple melodic phrases (an important one is fairly close to the DSCH Shostakovich theme, but seems to spell something different) and developing them with the control that Nosyrev can often seem to lack. It is a powerful, moving work. Like the Violin Concerto, it is beautifully and sensitively played. It should find a place in the concerto repertory as well as the record catalogue.

International Record Review, September 2001

This is the fourth issue devoted by Olympia to a composer previously hardly known in the West, and it confirms impressions of an attractive, middle-of-the-road but independent voice in Soviet music of the post-Stalin era. The two concertos come between his first two symphonies (on OCD 660) and just after the ballet The Song of Triumphant Love (reviewed in the July issue) and both are quality products. The epic 18 minute first movement of the 1971 Violin Concerto covers a wide expressive and stylistic range – from Szymanowski via Britten to something very close to Schittke – and its Presto finale restores a sense of balance with what sounds like a homage to the finale of Shostakovich’s First Cello Concerto. At no point does Nosyrev sound overawed by the models he invokes. Nor do his structures ever feel predictable; rather, a sense of deep-lying necessity impels them. This is a truly impressive achievement.

The Cello Concerto is a more introverted work, with two slow movements surrounding a central, moderately paced, folksy theme and variations. This may take a little longer than the Violin Concerto to get to know and love, but after three hearings I am convinced that the effort will be worthwhile.

Both soloists are excellent – intense and communicative in the best Russian tradition – as is the orchestral playing. Recording quality is vivid, and Per Skans’s essay is once again an attractive part of the package. If you are the slightest bit interested in the Soviet repertoire, and whether or not you have encountered the previous discs in this series, I do urge you to give this one a try.